INTRODUCTION

Balance and posture are interrelated. Depending on the base and the position of the centre and line of gravity a body is either balanced – in equilibrium – or not. Posture is the word used to describe any position of the human body. Some positions or postures require more muscle work to maintain than others, but whatever the position, balance must be maintained otherwise the force of gravity will impose a change of posture.

The maintenance of balance is dependent on the one hand upon the integration of sensory input from exteroceptors, proprioceptors and the special senses – the eyes and the vestibular apparatus – and on the other hand on an integrated motor system and the basic postural reflexes. In the normal individual, balance is maintained almost completely at a subconscious level. In retraining a patient's balance this fact must be considered and the patient trained to react to stimuli rather than to make a conscious, voluntary effort to maintain equilibrium. At times voluntary control will have to be exercised, but this causes the patient to be at a great disadvantage.

Balance, therefore, is the basis of all static or dynamic postures and should be considered when planning any exercise or rehabilitation programme. Its re-education should not be confined to patients with neurological conditions, as balance is frequently impaired following fractures, soft tissue lesions and surgical procedures involving the lower limb.

Balance reactions can also be used to facilitate the contraction of selected muscle groups and as part of a muscle strengthening programme.

There are two approaches to balance, both of which are necessary for normal function: static balance and dynamic balance.

STATIC BALANCE

The static balance approach is based on PNF principles and techniques.

Static balance is the rigid stability of one part of the body on another and is based on isometric and co-contraction of muscle. The rhythmic stabilization technique and the irradiation principle are used to develop a contraction of postural muscles. These techniques may be used in any position. They are frequently combined with compression to stimulate postural reflexes.

As a general principle balance is developed progressively by moving from the most stable to the least stable position, for example from forearm support prone lying to standing with sticks.

Stability and control of the head should be established first as these are vital in all positions. Strong neck muscles can then be used to reinforce muscle contraction elsewhere.

Assessment of the patient's muscle strength will guide the therapist in the application of the irradiation principle. Note that the possibilities of associated reactions and an undesirable increase in tone must always be considered. However, this method is useful with patients who are hypotonic or ataxic.

Application

As indicated above, positions for the retraining of balance are selected on the basis of progression from the easy to the more difficult.

Positions

Forearm support prone lying

Forearm support prone kneeling

Prone kneeling

Reach grasp kneeling

Half kneeling

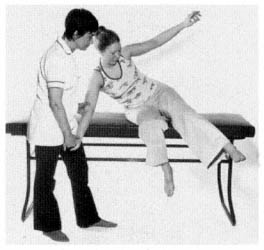

Sitting

Walk standing

Standing

Although in the normal development of the child standing is achieved before kneeling, for the adult, kneeling, and certainly reach grasp kneeling are frequently easier to maintain than standing. If required as a progression, shortened crutches may be used for support in kneeling.

In standing and walk standing the patient may be progressed from using parallel bars, through the range of walking aids to standing unaided.

Resistance is applied to all the components needed to maintain a particular position. Selection is made from the following:

• Head

• Shoulders

• Pelvis

• Knees

• Toes for gripping the floor

• Hands for gripping a support or a walking aid.

A slow increase of alternating resistance is used to build up a co-contraction, i.e. rhythmic stabilization. The direction of the resistance will vary with the point selected, for example:

(1) The pelvis

• Forwards and backwards

• Laterally

• Diagonally

• Rotation

(2) The knee

• Forwards and backwards

A combination of stabilizing points may be used to advantage, e.g. the shoulder and the pelvis, the head and the pelvis, the pelvis and the knee.

In some situations the principles of maximal resistance are used to stimulate a unilateral isometric contraction instead of a co-contraction; this is of particular value when working to obtain extension of the cervical spine in forearm support prone lying.

DYNAMIC BALANCE

This approach is based upon Bobath principles and techniques.

The body, unless it is fully supported and relaxed, is in a constant state of adjustment to maintain its posture and its equilibrium. The forces tending to upset this balance may vary in strength from the infinitesimal to sufficient to completely upset the individual's equilibrium so that he falls to the ground. Consequently, the body's reactions to maintain its equilibrium will vary in degree. For example, the amount of adjustment will be greater and more obvious when an individual slips on an ice-covered road than when he raises his hand to his mouth. The normal individual will find the former a difficult if not impossible exercise in regaining balance but he will not even be aware of the adjustments he makes when eating. However, raising the hand to the mouth will prove a severe test of balance for a paraplegic patient early in his rehabilitation, while he is still learning to compensate for the loss of sensory input from below the lesion.

At the level of minor adjustments, the muscles may be working either isometrically or isotonically but when larger adjustments are necessary the type of muscle work will become definitely isotonic. If one had to try to clarify this it is easier to work with the concept of static balance as being isometric, and dynamic balance as being isotonic contraction.

It is convenient to think of these balance reactions as occurring in two ways:

(1) An adjustment in tone to maintain a position.

(2) An adjustment in posture to maintain or regain balance. This can involve either movements designed to keep the individual in more or less the same place, or those in which the base is moved.

Maintenance of Position

This method, unlike rhythmic stabilization, allows for a little movement.

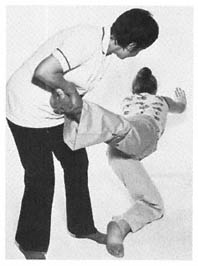

The patient is instructed to maintain the position, for example, prone kneeling, kneeling, sitting or standing against the therapist's tapping technique. This technique simply consists of tapping the patient's shoulders or thorax at shoulder level, first in one direction and then in the other. The tap should be strong enough to cause the patient to adjust his muscle tone but not strong enough to make him change his position. For example, when he is standing, a tap on the patient's back causing the body to move slightly forwards will cause the calf muscles to contract, a tap in the opposite direction will cause a contraction of the anterior tibial muscles. This is obviously an over-simplification as changes in muscle tone will occur elsewhere, particularly in the feet.

Maintaining or Regaining Balance

It has been said that our whole life consists of constantly regaining our balance. We are never static. One view of walking is that it is simply a transferring of weight forwards and that the leg moves to regain balance.

Balance reactions are immediate and reliable and are not learned at a voluntary level. Therefore, the therapist does not instruct the patient in how to react but puts him into such a situation that he has to react to maintain or regain his balance. It is usually a wise precaution to explain to the patient that you are going to work on balance, otherwise he may get very frustrated as most patients expect to be told what to do in the form of a definite task or exercise. Further instruction would destroy the patient's ability to react spontaneously.

The therapist must know the normal balance reactions, so that she will be able to recognize the abnormal and also so that she can facilitate normal reactions where they are absent.

An interesting point to note is the change of tone in a limb before it actually moves. The student can easily try this for herself. In the prone kneeling position do not move but think about lifting one hand from the ground and note the change of pressure and of tone. Without this preparation movement would not be possible.

The use of a moving support is valuable in some positions to facilitate movement and in others can be related to balance maintenance in such common situations as riding in a bus or car or on a bicycle or ship.

There are three basic types of movable support:

(1) A balance board, which can vary in size from the usual balance wobble board to a polished piece of wood 2000 mm long and 610 mm wide with a rocker at either end

(2) A roll, which can be made of a cardboard tube, as used in carpets, is padded and covered with plastic

(3) Large inflated balls of varying size and type.

Lying

This position is not usually associated with problems of balance but if the therapist wishes to stimulate movement, particularly trunk movement, the patient can be placed in lying on a polished balance board. The therapist controls the board from one end and tilts it so that the patient has to react to remain on the board.

From the age of 6 months a child will try to stay on the board. The disadvantage is that it is difficult for the therapist to control both the board and the patient.

Rolling a patient on a mat may be used as a method for reducing tone. A pathological pattern and the accompanying hypertonus is a complete entity. General reduction in tone as a preparation for movement starts with efforts to produce symmetry and trunk rotation. Trunk rotation is lost in patients with Parkinson's disease and trunk rolling can be used followed by the rhythm technique. Following the reduction in tone, active balance reactions occur. These movements, in themselves, tend to reduce tone still further. Even where hypertonus is not a problem balance reactions in lying may be used as a form of exercise. There are several ways of producing trunk rotation passively but to activate the patient the following methods will form a basis for stimulating activity.

The patient is placed in lying with the therapist kneel sitting so that the patient's head is resting on her knees.

The patient's arms, when possible, are placed in the flexion/abduction/lateral rotation position which is a reflex inhibitory pattern, i.e. a position opposite to the basic pathological pattern of spasticity. This position in itself will tend to reduce tone as a preparation for movement. The therapist places her hands high on the patient's scapulae and rolls him first to one side and then to the other. Once the patient begins to show some movement more time is spent with him in the side lying position. The therapist slightly adjusts the patient's position, constantly putting him off balance so that he has to move either his trunk or the upper leg to regain his equilibrium .

This method can prove impossible if the patient is too heavy to move from the supine position. When this is so, side lying can be used as a starting position to activate balance

Comments